Unfinished Business: War ended Pepper’s career too soon

/

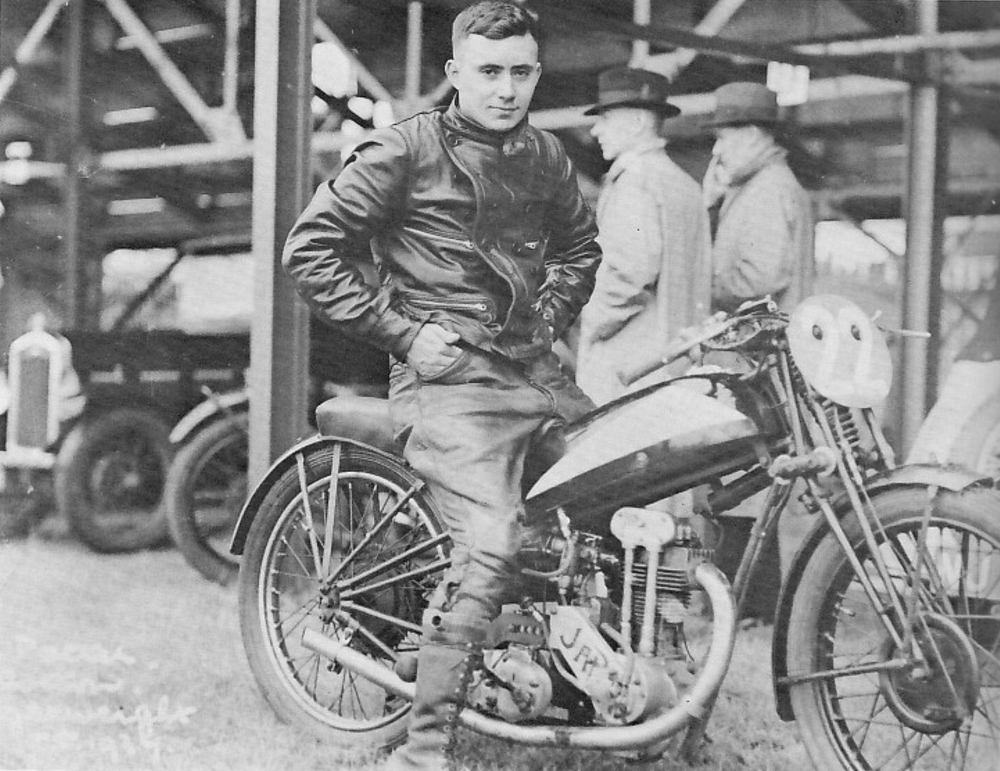

In the mid-1930s George Pepper was recognized as one of North America’s top motorcycle racers.

By John Hopkins

Photos courtesy of Vada Seeds/Canadian Motorcycle Hall of Fame

Residents of downtown Belleville awoke to an unusual sight on the morning of Labour Day, 1936. If they lived on Yeomans, Moira, Everett or Catharine Streets, they found snow fencing and haybales in front of their homes, lining the roadways. If there was any confusion as to the purpose of these barriers, it would be erased soon enough by the cacophony of 35 motorcycle engines leaving the startline as the inaugural Canadian 200-Mile Motorcycle Roadrace got underway.

While the event itself has a prominent place in Hastings County sports history, a more lasting legacy was shaped by the race winner, local hero George Pepper. The Belleville native scored a convincing triumph, finishing almost 10 minutes clear of American star Babe Tancrede after nearly four hours of racing. The victory would help propel Pepper to an international racing career that was cut short by the outbreak of World War II, in which he distinguished himself as a top pilot with the Royal Air Force before his death in a training accident in 1942.

Interestingly, the Belleville roadrace was one of the few occasions Pepper’s racing luck actually held out, otherwise his legacy might have been much stronger. The son of a prominent amateur hockey and baseball player, Pepper first made his mark on the Canadian racing scene in the 1932 Canadian Tourist Trophy in Toronto, where he was running among the leaders before his engine seized near the finish. A few months later he finished third in the American 200-Mile roadrace event in Jacksonville, Fla., just one and a half seconds behind the winner. In January, 1936, in the American Motorcycle Club’s 200-mile event in Savannah, Ga., Pepper led the field of 71 racers nearly all the way before he was forced to make a pit stop for machine repairs and dropped to fifth.

Later that year, in July, 1936, Dr. J.A. Faulkner, the MLA for Hastings West, received permission to hold a major motorcycle race through the streets of Belleville. The exact route of the event, however, was not announced until the day before the race to reduce the chance of protest from local residents. The event attracted the cream of the North American motorcycle racing crop, including Woonsocket, R.I.’s Tancrede, the 1935 U.S. champion, riding a Harley-Davidson.

George Pepper’s big international break came in 1937 when he participated in the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy races. Although he failed to finish any of his races, he found steady work riding Speedway in England soon after.

Aboard his British-built Norton, Pepper surged into the lead on the 16th of 120 laps around the 1.8-mile track and steadily increased his advantage from there to take a convincing victory.

The event itself proved to be a huge success, with a crowd estimated at 20,000.

“Historic circus parades which have drawn many thousands to the streets paled into insignificance as the race drew the vast crowds who surrounded the course,” wrote Paul Kirby in his book Champions All – A Sports History of Belleville. “In places the people were so thickly packed that few more could have found standing room. Along Everett Street, especially on the east side of the roadway, there was a large crowd.”

Rather than provide the springboard to more victories, Pepper’s Belleville success unfortunately proved to be an isolated bright spot in a frustrating career. A month after his Labour Day triumph, he was invited to participate in the inaugural races at New York’s Roosevelt Speedway, but running in second place late in the 45-mile event he crashed.

Despite this latest setback, Pepper had done enough to chase racing success further afield, and in May, 1937 the 24-year-old sailed from Montreal to compete in the famed Isle of Man Tourist Trophy. Although the races on the Isle of Man have dwindled in prestige since they were removed from motorcycle’s World Championship in 1976 due to safety concerns, they remain a daunting test for rider and motorcycle. The TT course covers some 37 miles of the island, located on the Irish Sea, and takes riders through villages and over mountain passes.

“My first impression on seeing the course was a feeling of doubt as to whether or not I would make a fool of myself in the races,” said a typically modest Pepper in a letter to The Intelligencer sportswriter Ken Colling, “as it looked almost impossible to average even 60 mph let alone a speed like some stars of over 88 mph.”

Pepper’s reputation had caught the eye of the prominent Norton motorcycle manufacturer in England, which agreed to provide the Belleville newcomer with a new motorcycle and a seasoned mechanic, himself a racer with experience on the Island.

Pepper methodically worked his way up to speed during practice for his three races, but once again his luck let him down in competition. He was forced out near the end of his first race with engine problems, then suffered a similar fate in the Lightweight race. In the Senior TT, the most prestigious event of the week of competition, Pepper suffered a fuel leak on his opening lap and once again had to drop out.

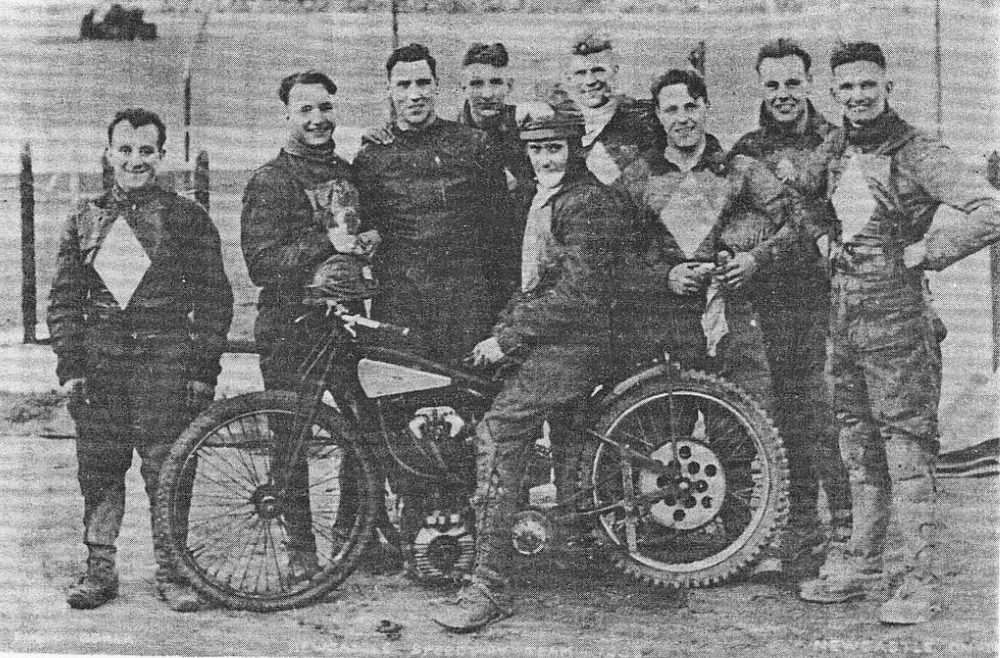

A disillusioned Pepper was prepared to return home before a fellow Canadian intervened, and his racing fortunes took a decided turn for the better. Toronto’s Eric Chitty persuaded Pepper to join him in the popular team-based British Speedway league, where crowds ranged from 20,000 to 60,000 a night. As part of the West Ham squad, Pepper started out as a mechanic and then rose to the position of spare rider before taking over a regular spot when Chitty left to race in Australia. According to Champions All, Pepper was eventually earning about $400 a week, well above the average of $200 a week most riders managed.

In 1938 Pepper moved to captain a new Speedway team in Newcastle, which he led to the Second Division title in its first year. By now Pepper had achieved superstar status and was a nationally-recognized sports figure.

“Before too long, he was indeed the idol of the crowds – newspapers announced where he would be making his public appearances,” Kirby wrote in Champions All. “He was also one of the top riders in the country. In addition, he was chosen to pick an all-Canadian team.”

As captain of the Newcastle Speedway team, Pepper (on bike) led the squad to the Division Two title in 1938.

The onset of war brought an end to Pepper’s racing exploits, just when he was enjoying his greatest success. Initially he worked as a mechanic building Spitfire airplanes but in September, 1941 he earned his wings as an RAF pilot and joined a night-fighter squadron.

“Night-fighting is totally unlike any other kind of modern aerial combat or operation,” an RAF officer is quoted as saying in Champions All. “The day fighter tackles his adversary during the hours of light; the bomber-boys, even at night, attack a target which can’t duck or hide or run away. But the night-fighters pursue a quarry beside which a will-o’-the-wisp is a gigantic flaming beacon.”

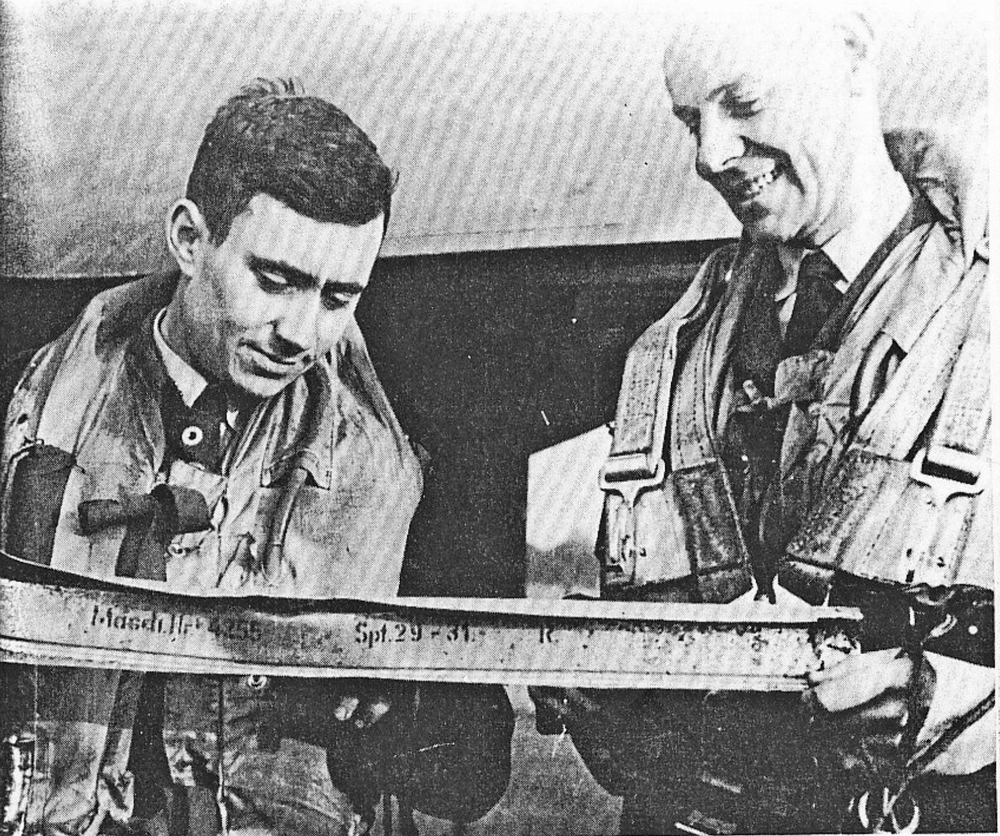

On All-Hallows Eve of 1942 Pepper and his partner J.H. Toone (the duo was known as ‘Salt-And-Pepper’, apparently thanks to Toone’s light coloured hair) distinguished themselves by shooting down three enemy Dornier aircraft, a feat that earned Pepper the Distinguished Flying Cross and Toone the Distinguished Flying Medal.

Barely two weeks later, however, on Nov. 17 the 29-year-old Pepper was killed in a daylight test crash along with Toone and a boyhood friend and fellow motorcyclist, Jack Embury, who had been visiting Pepper in England.

Pepper and J.H. Toone (right) were honoured for shooting down three enemy aircraft on a single night in the fall of 1942.

Pepper’s funeral was held in Christ Church in Belleville on Dec. 19 and his ashes buried in the Belleville Cemetery. Last November he was inducted into the Canadian Motorcycle Hall of Fame, which described him as “one of Canada’s most naturally-talented motorcycle racers of the prewar era.”

While his international reputation was still growing at the time war broke out, the prestige he brought his hometown of Belleville is undeniable, and that is in large part thanks to that Labour Day race in 1936 where he vanquished the best motorcycle racers in North America.